Ancient and medieval papyri not only transmitted text, some even held illustrations. Mathematical, scientific, and magical papyri often had accompanying images meant to enhance the understanding of a text or perhaps to depict someone being cursed. Some historical and literary papyri (e.g., those of Homer) had illustrations as well. I was reminded of this fact this morning, as I reflected on the death date of the notorious Alexandrian patriarch Theophilus, who died on October 15, 412 CE.

We are lucky enough to have the Papyrus Goleniscev, a codex (fol. 6v, Pushkin Museum, Moscow) that was later published in color in 1905 (digital edition here) and then digitized by the Munich Digitization Center (Münchener Digitalisierungszentrum [MDZ]). The papyrus is originally from Alexandria, and perhaps dates to the 5th c. CE–not long after the death of Theophilus himself. The papyrus transmits fragments of the Alexandrian World Chronicle and has a pivotal depiction of the patriarch holding a gospel and standing atop the head of the Egyptian god Serapis, which had been destroyed along with Alexandria’s Serapeum.

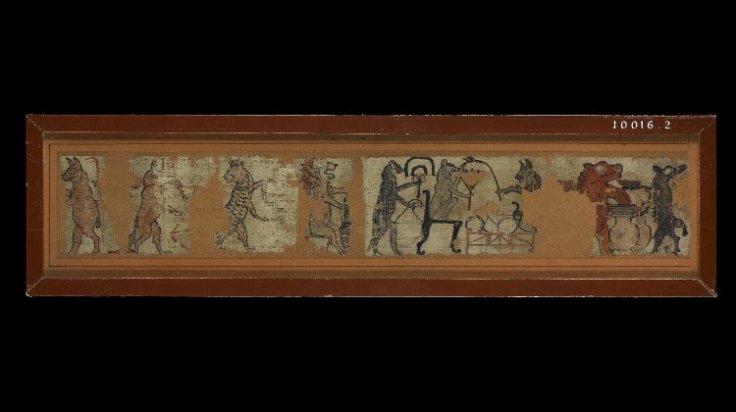

The painting of papyri has been happening for millenia, and reveals not only what may have been important to those that painted them–but also what people found humorous. Over at the British Museum, they have one of my favorite papyri of all time, dating to the period of Rameses (1292 – 1077 BCE) and from Deir el-Medina (Thebes). It shows various animals engaged in common Egyptian trades: there is a hippopotamus and then a lion brewing beer, a cat serving a mouse, and a dog carrying grain. I like showing this papyrus when I give talks on ancient beer or in class, just to illustrate to students that anthropomorphized animals were amusing to people way before LOLZ Cats came around.

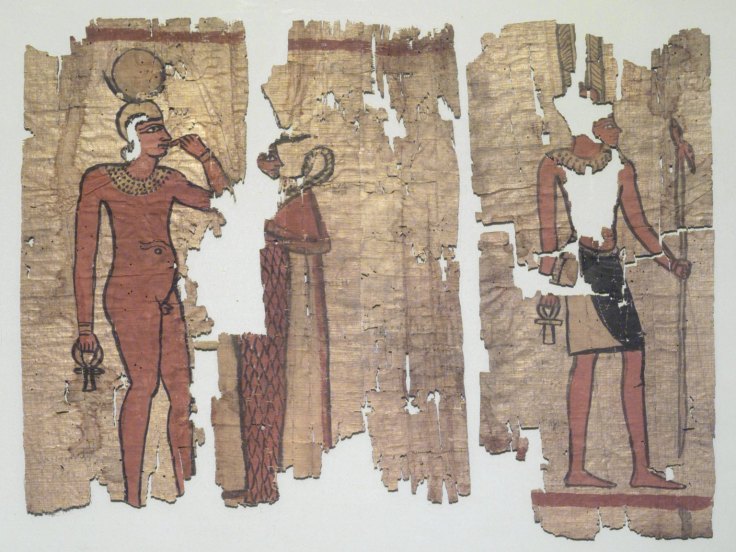

There are some beautiful images of Hellenistic era papyri (4th-3rd c. BCE) in the collection at the Brooklyn Museum as well. What is more? The Brooklyn Museum has placed their images under a creative commons license, which allows me to show you this stunning procession of Egyptian Gods below.

The ability to look at this papyrus online with students or to use it for research purposes is a valuable one–but it comes with some caveats. Particularly, we must consider how an image can be used: in publications, in the classroom, and online. Licensing is something I have thought a lot about since beginning to blog at Forbes, but many images I cannot use simply because they are not available for free use by commercial outlets. I understand this sentiment completely, but it means I have to be very careful about the images I post at Forbes, which is a for-profit news corporation, versus my WordPress blog, which makes me no money. That is why I appreciate the clear use of Creative Commons licensing that marks how I can use an image. For the MDZ, who digitized the 1905 edition of the Papyrus Goleniscev, there is a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license that stipulates that I must note the institution and if I modified the image, and bans me from using the image for profit. Hence why I am writing this post on my WordPress blog.

I started thinking about CC licensing this week largely because Dot Porter (Curator, Digital Research Services, in the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at the University of Pennsylvania) pointed out on her blog that it is frustrating when an institution says that texts are “freely available online” and then does not clearly delineate what they mean by this. In her post, she lists a number of questions one should answer when posting digital images (e.g., are your images licensed?) and does a fantastic job of laying out the logistics that need to be thought through when museums, libraries, individuals, or institutions disseminate digital images online.

Licensing is important for blogging, but also needs to be integrated into our Twitter lives. For a long time, I have been trying to do a better job of citing the sources for my images on Twitter and encouraging others to do so as well. I try to use my own pictures from museums or those freely available on Wikimedia, and to give attribution to people when I use Flickr photos or perhaps pull from their personal blog (e.g. Following Hadrian’s Carole Raddato, who is incredibly generous with her images). Other digital humanists, like Alice Lynn McMichael at MSU, have also begun to think about how Twitter licensing and tags can help us to use Twitter content for use in linked open data digital projects–like Pleiades.

Many on Twitter pointed me to the fact that Twitter has a description capability for images that was originally put in place for people with visual disabilities. As Twitter notes: “Enable this feature by using the compose image descriptions option in the Twitter app’s accessibility settings. The next time you add an image to a Tweet, each thumbnail in the composer will have an add description button. Tap it to add a description to the image. People who are visually impaired will have access to the description via their assistive technology (e.g., screen readers and braille displays). Descriptions can be up to 420 characters.” Twitter’s “image descriptions” function is a fantastic resource that we all need to use more. My hope is also that Twitter will begin to add machine-readable tags (e.g. as they do at Flickr) that will allow images posted through the social media service to be better archived and used by DH projects.

This post has certainly been a mix of ideas and topics, but licensing ideas have been brewing in my head for awhile (by me, not by an Egyptian hippo). This morning seemed as good a time as any to begin a deeper conversation on the importance of clear image licensing. It is also a chance to say thank you to those digital preservation librarians who work tirelessly to provide these images for public use. In my teaching demonstration just two years ago, while interviewing at the University of Iowa, I taught a passage of Homer directly from a papyrus image provided by the Homer Multitext Project. The students relished the ability to see how some of Homer’s texts were transmitted and to read the original papyrus–in all its funky handwriting. Having access to papyri while sitting at a desk in Iowa City has been an invaluable resource, but clear licensing by posters and clear citation by users is part of maintaining healthy digital relationships and respecting each other’s work.

Digital Resources for Papyri:

Duke University, Papyri.info (check out their list of papyrological resources here).

University of Michigan Papyrological Collection (Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license)

Digital Papyri at the Houghton Library (Varying in copyright, but largely in the Public Domain).

Fantastic Papyrology Blogs

Roberta Mazza, Faces and Voices

Leave a comment