It was my pleasure to attend the annual meeting of the SCS-AIA in San Francisco from January 6-10. I just got back to Iowa City last night, and wanted to write while the thoughts about the conference were still fresh in my mind. First, I want to say that the SCS-AIA always serves as an annual pep talk to get attendees energized for the year ahead. I heard exceptional papers ranging in subject from the Greek economy to the archaeology of weights and measures, and loved being reminded of the myriad digital, technological, and methodological innovations afoot in the field of ancient history. Additionally, there were more Late Antiquity (200-800 CE) panels and papers than I have ever seen before. This shows real progress towards better incorporating late antique history and patristic studies into the field of Classics.

Those were the positives; however, there were also some negatives. On Thursday, I attended a meeting wherein I was told by a senior scholar that affirmative action and the target hiring of women for specific positions was no longer relevant or even necessary, because racism and misogyny were now quite rare in academia (Good to know! I disagree completely!). I stayed after the meeting to debate this point with said scholar further (35 minutes), but was quite upset even to have to defend myself. I am proud to say that his is the minority view at AIA-SCS, from what I have seen, but it was a reminder that such individuals still exist and still have influence.

What was a bit more troubling, was to find that there were a number of all male panels on the program for the conference. Now, some of these were panels put together by blind review of abstracts–i.e., there was no knowledge of the gender of the person ahead of time–while others were organized panels where presenters had been asked ahead of time. Although their numbers have been decreasing for many years, the all male panel is an animal that still has not been made extinct, either in the field of ancient history or in many others. The New York Times has pointed out its existence in media, news, and politics, but it lives on in academia as well. In fact, one of the most popular webpages on this topic is the hilarious “Congrats, You Have an All Male Panel!” TUMBLR, which lays out its aims thusly: “Documenting all male panels, seminars, events, and various other things featuring all male experts.” Meeting participants are asked to send in pictures of their all male panels to the TUMBLR, where it will be stamped with a picture of David Hasselhoff–a “Hoffsome” stamp.

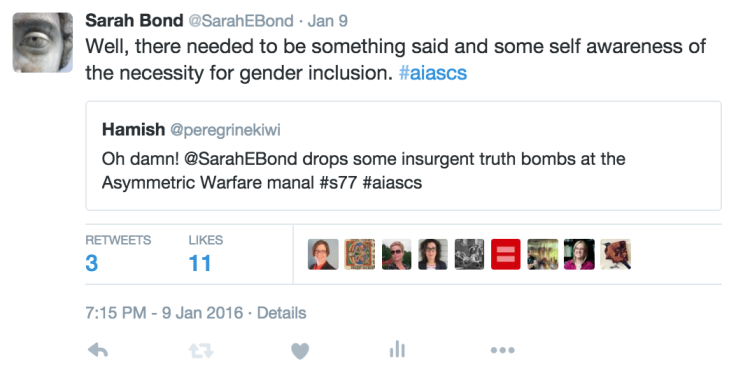

When I was asked to give a paper for a sick (male) friend at an ancient military panel on Saturday, I was exasperated to find that it too was a classic”manel”. The organizer and the panel consisted of kind, good scholars, but I felt like the whispers and the secret complaints of female academics usually only heard on Facebook or over early evening martinis at the conference hotel bar needed to be voiced.

Around 25 people populated the room, with 3-4 women (depending on the paper) in the audience and, well, 21 men. When it was my turn, I asked to speak to the ladies (“Ladies, can we talk?”) in the room and point blank told them that they should take the initiative and introduce themselves to the men in the room after the panel (“Tell them what you do! Ask them if there is a chance you can work together in the future!”). To the credit of the men in attendance, there was only one audible sigh (with visible eye roll for full effect), while everyone else just nodded and looked uncomfortable about my harpooning the elephant in the room. No matter! The paper went off well, and then we all had a good talk afterwards. I was relieved, but my carefully picked power dress had the biggest underarm sweat stains I can remember.

There are a number of reasons why these all male panels occur quite frequently in the field of Ancient History. One thing to remember is that the blame is not always on the shoulders of the old-boy network.

1. Ancient history has had a problem with attracting women–particularly in military, economic, and political history–for a long time. By my count, for every 7 men or so in these ancient subfields, there is 1 female ancient historian. This is better than it was in the 1970s, but still not good. One time, at a meeting of the AAH (Association of Ancient Historians) at Chapel Hill, I ran into a legendary female ancient historian in the bathroom. While the men’s line was out the door, it was just she and I in the rather large bathroom. She looked at me and said, “At least there is one plus to being a woman in this field: You never have to wait in line for the toilet!” Quite right. Simply put? We need more women to actively choose to work on Roman coinage, battlefield logistics, or late antique Visigothic law! If women don’t go into these fields, they can’t participate in the panels and the participant pool will remain largely male.

2. People pick their friends for panels rather than searching out others they may not know. Look, when you organize a conference, a panel, or a colloquium, you often go to the people you trust the most: your friends and the people whom you or your advisor has worked with before. I have done this. You have done this. We have all done this. The important thing to see is that having women visible on academic panels and on executive committees will encourage more women to follow suit and to get involved. Make an effort to seek out a female graduate student or professor rather than defaulting to the normal network. Men: Challenge yourself to incorporate women. Women: Challenge yourself to introduce yourselves to men in positions of power. I hate saying “lean-in”, but damn it: Lean In.

3. Female historians are seen as people who do “soft” history: The only time I usually see an all-female panel in Ancient History is when it is on the topic of “Women in Antiquity” or perhaps”Gender and Sex in the Ancient World.” Those are important topics, but that is not all we do. I know some badass women (e.g., Constantina Katsari) who can break down Roman economic history with the best of them. Also remember: All female panels can be just as bad as an all-male panel.

Early this morning, I was pleasantly surprised to receive an email in my inbox. The convener of the aforementioned military panel wrote to ask if I could introduce him to any women who specialized in ancient military history. I thought, “Um, yeah. Absolutely, dude.” I sent him a few names, but I do think there should be a better way to do this than just word of mouth. What if the AAH, the AHA, the SCS, ASGLE and the AIA all had a list of women willing to serve on panels, committees, or subgroups?

I have begun to compile a list of women in ancient history and invite you to add names to the list. It is an editable Google doc available here. Please contribute and comment. Let’s get this conversation started and make sure that next year we can make even more progress towards gender inclusion in Ancient History.

I think the onus should rest far more on the privileged members of the field to reach out to, incorporate, and research non-privileged members. And that includes the panel chair, who in asking you for a list basically puts the work *they* should be doing on the shoulders of you and the people who will ultimately be on that list. I think, in issues of gender disparity in social groups, it is easy to invoke a gender-stereotyped lack of “assertiveness” as (part of) the cause for the disparity, which then makes it easier to blame women for their lack of inclusion in masculine spaces. In non-gendered instances of disparity in social groups (e.g., racist or ableist privileges), the notion of “assertiveness” or “leaning in” is hardly ever invoked as a causal factor. Which is to say I’m completely in your support, *and* I think that we should be questioning where the labor and blame gets placed when disparity persists.

Great points, Lisl. I quite agree.

Sarah, you go girl! You know, we could just organize our OWN panel! Actually, thinking back over the years, one area that surprisingly does quite well with mixed gender, and you wouldn’t think it would, has been Roman law panels….so there’s hope….it was great to see you sis!

Yes, we can! Let’s talk about SCS or AAH 2017. I agree that Roman Law has amazing women. You, Caroline Hunfress, Elizabeth Meyer, and many more. Your work and you inspire me all the time and I am so glad you are my academic sister. Rock on, soror.

As one of the 3-4 females in the room with you, I appreciated your comments. I work at the US Naval Academy, and I am one of 6 women (two of whom are leaving next year) in a department of 45 or so. I took your advice to heart and hung around after the panel for conversation, and got some great ideas for collaborative classes to teach on ancient military topics that I’m sure my students will love.

That is so awesome! Thanks for coming. You rock.

I was one of the three female speakers at an entire AAH conference a few years ago, two of us in separate panels and one woman giving the keynote. It felt conspicuous – and I was speaking about war memorials, although I generally admittedly do so-called “soft” history of gender and sexuality. I’d be happy to serve on committees or subgroups as requested for social history (quantitative, with humbers even!), cultural history, reception studies, etc…

I also note that it doesn’t help that the SCS and related convention culture is parent-unfriendly as well as problematic with regard to women. I just successfully navigated the hurdle of obtaining babysitting from 10-11 PM in San Francisco so I could attend receptions, but it was not an easy task. Meanwhile, the AHA offers a nursing mothers’ room and $250 of childcare, as well as resources available to locate a sitter during the entire conference.

This is great feedback. I am writing this down and will pass it onto the AAH president, Lee Brice. He is very receptive to female ancient historians… Particularly because he is progressive, understanding, and married to one.

Yes! Seconding what Anise said! The profession seems to treat us as nuns, effectively, and it is very difficult to remain an active academic once a mother. As a mother of a 10-year old and now a 7-month old, I have been able to continue writing and publishing (you know, the stuff that I can do largely from home with the support of a wonderful husband), but conferences have taken a back seat since the baby has arrived. I have thought before of organizing a roundtable discussion on mothers in academia, but I worry that none of us would be able to attend our own roundtable without childcare on site!

Thanks for this, and I will send along your comments to the AAH president. I also agree that both societies need to work on providing healthcare. That is a major service that can facilitate the participation of more women in the field.

At some point I started a mini-study to see how the gender of organizers affected the gender of participants in organized AIA panels (https://englianos.wordpress.com/2014/03/13/gender-disparities-in-archaeology/). Basically, I found that “in panels organized by one or more men (and no women), 66% of the speakers were male; in panels organized by one man and one woman, the speakers were 50% male; and in panels organized by one or more women, 47% of the speakers were male”. That’s pretty bad, but I suspect that it may be worse in other fields of Classics (like ancient history, maybe?) and certainly it’s worse in other disciplines. It would be interesting to track it diachronically and to see how it compares to the gender percentages in open panels (which I didn’t do).

I agree. My friend Maren Wood did all the AHA & Chronicle stats for humanities job placement, so we are in talks to see what can be done about tracking gender in panels. This is a great start and I am sorry I didn’t know about it before I wrote this!

A couple of years ago, Paul Cornell (who is nobody in ancient history, but a big name in comic books, Doctor Who, scary fantasy novels, and British sci-fi) said he would refuse to be on any panels that weren’t at least half women. When he was put on one anyway, he stepped off the dais and gave his seat to a woman in the room who he knew as much or more about the topic that he did.

More men should follow his example. Thanks for the link to the “Hoff” bestowing Twitter. Sorry for the inclement weather, but we really need the rain.

As the badass economic historian I am (thank you Sarah for a term that will be stuck in memory and history for a long time), I felt obliged to comment on this excellent post. I remember more than a decade ago, I participated in a conference in New York. It was on monetary economics and it included more or less everyone in the field. Among them it was myself and Ute Wartenberg, the only women in the room. To tell you the truth I have not noticed the absence of women, because I was concentrating too hard on the theories that were debated and the new ideas that were bouncing around. I became aware of my gender only when I entered the elevator to go to another floor. Suddenly, I found myself surrounded by 12 male ancient historians, all of them a couple of heads taller than me. I distinctly remember feeling claustrophobic and getting into a ‘fight or flight’ mood. This is probably the only time I ever felt intimidated in a conference. After that, I actually relished the fact that I was the only woman in the room.

The story continues now. After leaving academia two years ago, I find myself alone in the room again! I am building tech startups and advising tech high growth businesses. Innovation and entrepreneurship is enjoys about the same ratio of men:women as ancient economic history. I feel extremely lonely (again) and I keep rooting for the few women that pass by. To no avail. What I learned after all these years in male dominated fields is to relish being different. I have also learned how to take control of the discussion and not being upset when they try to ignore me. Ignore me! Ha, as if…

The title of badass economic historian is well deserved. Each time I have taught my slavery class, I tried to get more gender balance in my assigned readings. You certainly showed me that women could do economic history and the history of slavery (along with people like Sandra Joshel), but that is the whole point: visibility of women inspires other women to follow suit. And yes, it is probably very hard to ignore either of us now.

If only one in eight scholars in ancient history is female, wouldn’t a panel of four people be all-male roughly half the time if you put it together disregarding gender (which, I assume, is the aim)?

I understand it has benefits to a diverse group of people (regarding gender, race, age etc.) discussing, so I don’t want to argue you should do more all-male panels. Rather, attracting more women is the right thing to do. It just seems to me that if there are more women in panels or as speakers than is proportionate it’s really a point of debate whether it’s more important to have women (or other minorities) visible (which has positive effects, hopefully) or if it’s more unfair to male (or white or 50+ or whatever) scholars who have a lower chance to be selected because they are men (or white or 50+…).

I’m not an ancient historian and have no vested interest and I’m sure it’s a somewhat crude point to make, but I’m still interested in this kind of question.

“[W]hen I’m sometimes asked when will there be enough [women on the supreme court]? And I say ‘When there are nine.’ People are shocked. But there’d been nine men, and nobody’s ever raised a question about that.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

David, as a fellow white male professor, I cannot overstate how little I care about being “unfair” to white men (much less white men over the age of fifty) in this context. Perhaps once the profession has systematically discriminated against, disenfranchised, overlooked and otherwise undercut white men at virtually every turn for the next several hundred years, we can talk.

I’m not suggesting that turn-about is fair play here. What I am saying is that Dr. Bond’s *extremely modest* suggestion of including more women in a male-dominated field is hardly unfair. A panel boasting 50% women (regardless of how many older white men are upset about it) is hardly unfair. Moreover – as per the Notorious RBG – an all-female panel is hardly unfair, either.

Part of why only 1 in 8 scholars in ancient history is female is that male historians make being a female historian absolutely miserable. I am frequently the only female on my panel, and I can’t count the number of times a (senior male) fellow participant has basically said to me “But aren’t you wrong?” Male participants never get asked this question; they get cards and networking.

Younger male historians are often, but not always, better. Female historians are always better: if they disagree, they offer constructive criticism. I don’t mean to say that male historians never offer constructive criticism, but it is entirely true that only male historians offer *destructive* criticism.

Reblogged this on iheariseeilearn.

I was just mentally reviewing the panels I’ve been on, and I’d say a majority of them were mixed-sex, and on a good number of them, I’ve been the token male. For some reason, a lot of the people who work in medieval heresy are women.

{sesli sohbet seo}güzel bir makale paylaşımı olmuş başarılar.

could my name be added to your list?